“We don’t believe that fine wine can ever be the outcome of a formula, a recipe, or of scientific winemaking.”

—Chris Howell

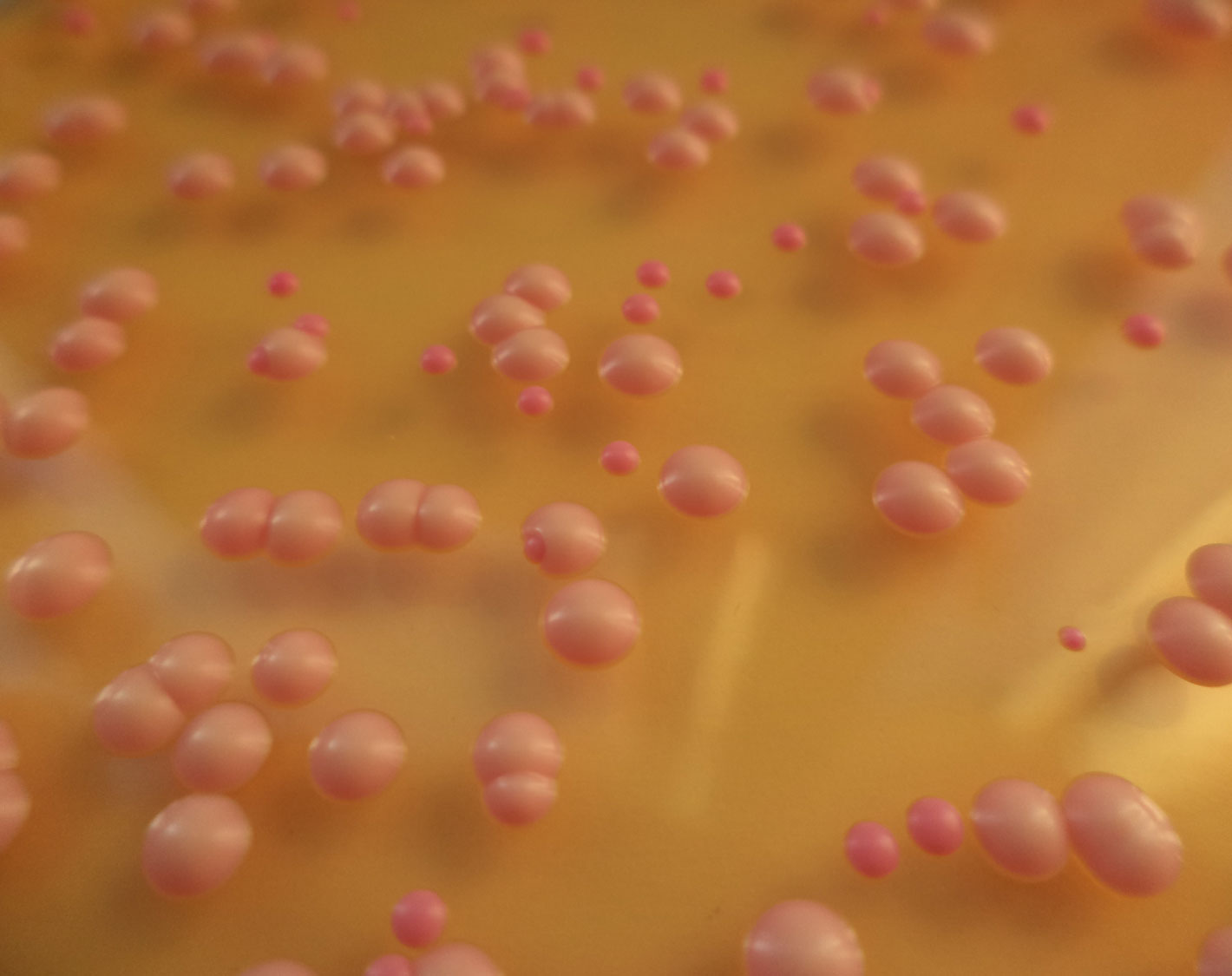

There are those, well-trained in identifying a litany of flaws to which a wine might be subject, who are able to identify the unmistakable signature of the yeast Brettanomyces, affectionately called “Brett,” usually thought to be a flaw. If a wine were only about Brett, that would be a problem, especially if it were pure barnyard. But for us, it isn’t—we find much more than any single element to define this wine. To those who simply can’t abide any hint of Brettanomyces, we respect your opinion.

To our way of thinking, the presence or absence of Brett is not a flaw per se—rather, it’s an attribute. Just as with perceptible oak, oxidation, or volatile acidity—all possible elements in a wine—we believe that nothing should stick out, and no one thing should be the defining trait. It is all about balance and harmony.

We identify the aromas produced by Brett with the yeast itself, however it’s not that simple; the linkage is not direct. It should be noted that it’s not the Brett yeast itself that is the potential problem, but the aromas it can create, literally ranging from floral to fecal (from roses to shit), politely called “barnyard.” It is this complex expression of Brettanomyces and the way in which its metabolites can be experienced—the ways in which they are integrated into and become one with the wine—that make it exasperating for wine chemists to pin down, and sometimes, wonderfully fascinating to lovers of “Old World” wines.

However, Brett was never limited to the Old World. Not so long ago, it could be found from Burgundy to Australia, by way of the Rhone Valley, the Loire, Bordeaux, the Rioja, and the Napa Valley. First clearly identified in the late 1970s as a “spoilage yeast” in some red wines from the Napa Valley, wine chemists embarked on a campaign to eradicate Brettanomyces, first at wine schools in the New World, such as UC Davis in California, and Roseworthy in Australia, and then in the Old World, at the University of Bordeaux. Today, among wine technicians the world over, Brettanomyces is anathema. On the other hand, some wine lovers are wondering, what’s missing?

Many knowledgeable people will say that it’s a matter of degree. A small or limited amount of Brett might be okay if it were to add complexity. However, if there’s too much, it can overwhelm the wine. But we see many dimensions. Brett is not monotonal—it is not one thing. Indeed, it is far more interesting, far more aromatically diverse. Just as with a malolactic fermentation, the outcome of a Brettanomyces fermentation is not a single molecule or aromatic note, such as “buttery” or “manure.” If it were that simple, the discussion would be limited to the appropriateness of that single note within the context of a given wine.

In our experience, the outcome of a Brett fermentation is far more complex and varies widely according to the wine and the timing of the fermentation and the subsequent aging of the wine. What are the factors? We have only begun to hypothesize: the vineyard, the strain of Brettanomyces, the composition of the must, the ambient conditions of the cellar, trace levels of residual sugar, the polyphenolic structure of the wine. How do these factors interact? We have almost no clue. One reason why we know so little is that most research and practical experimentation has been directed toward eradicating Brett. Although very little has been done yet to learn how to work with it, Linda Bisson’s lab at UC Davis is one of the first to work in this extremely interesting and promising field.

We don’t believe that fine wine can ever be the outcome of a formula, a recipe, or of scientific winemaking. If wine were reduced to a formula, it would be a mere commodity—and most of it is. But fine wine is the result of a subtle interplay between humanity and nature, one that has been going on for thousands of years. Wine could not exist without people, yet the wines we love are not only about people, they are also about nature. In the world of fine wine, each vineyard, each vintage, each vigneron, and each cellar is different. In the world of fine wine, humanity becomes one with nature. While they may be interesting, not all differences are necessarily good or enjoyable. But we don’t want all wines to taste the same, so we search for the differences we like, and we celebrate them.

Once you get rid of something, then you want it back. Isn’t that always the way? “Be careful what you wish for.”

—Christopher Howell, Wine Grower

Copyright, Cain Vineyard & Winery 2014